A Media Art Conceptualism in Latin America in the 1960s

Reflecting on the problematic term "Latin American Conceptualism," Harper Montgomery'south text stems from a workshop at MoMA in which she and the C-MAP Latin America inquiry group debated some of the issues surrounding the historicization of experimental art in Latin America. The workshop raised a number of questions that are broached beneath.

This text was office of the theme "Conceiving a Theory for Latin America: Juan Acha's Criticism." developed in 2016 past Zanna Gilbert. The original content items are listed here.

We all know that language is enormously important. For art historians, the terms we cull to describe art can significantly touch how information technology is interpreted and valued. When artworks are deemed "conceptual," they are inserted into an international field, and comparisons betwixt peripheries and centers get unavoidable. While these comparisons may not always be justified, they are oftentimes useful because they help us parse how like artistic concerns—such as the desire to abandon painting and sculpture and to intervene in social contexts outside art galleries—took unlike forms in different places. Whether or not we intend to, when we employ the terms "conceptualism," "dematerialization," "arte no-objetual," etc., comparisons are implicitly drawn.

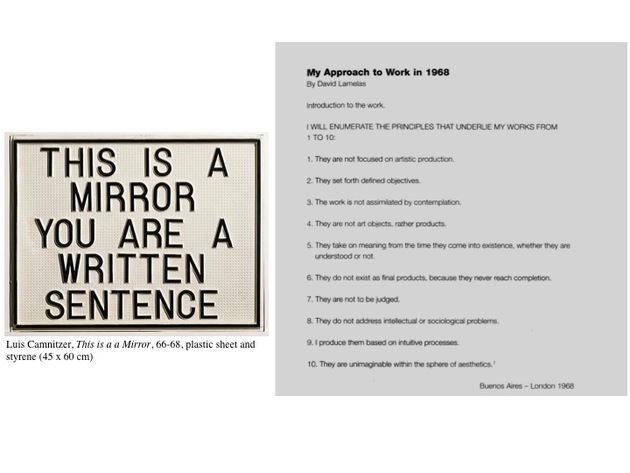

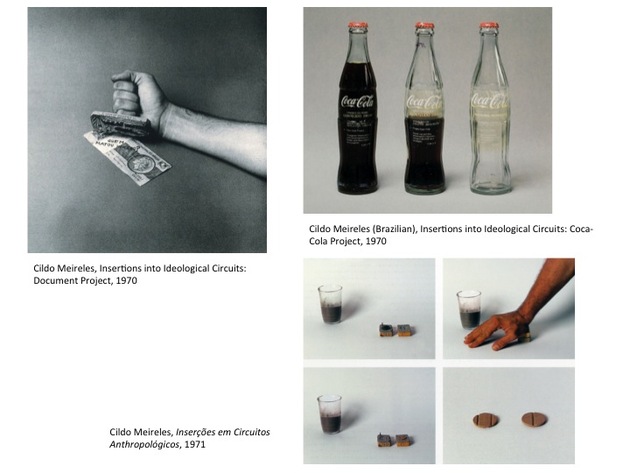

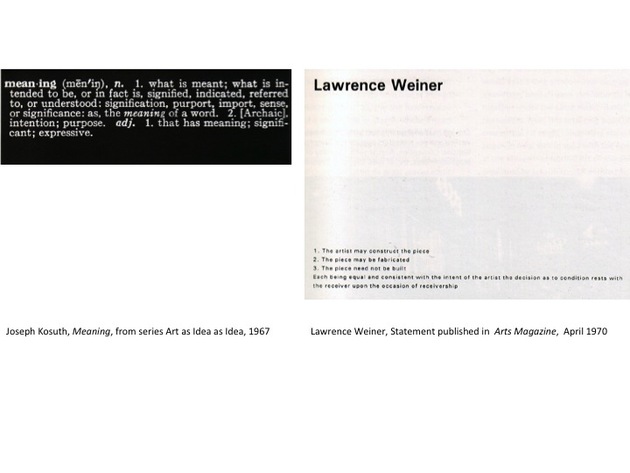

Comparison is the basis of the widely held and often stated view that conceptualism adopted a more political posture in Latin America than it did in the Usa. The statement claims that while Latin American artists responded straight to the sociopolitical events of the belatedly 1960s and early 1970s, in New York, artists' critiques were more circuitous because they were ofttimes inscribed within the institutions of the museum and gallery. For example, the art market was the target of projects by Joseph Kosuth, Lawrence Weiner, and others at Seth Siegelaub'southward gallery in New York during the late 1960s, whereas Cildo Meireles intervened direct in the economic and political systems that control people'southward lives during Brazil'southward military dictatorship in his serialInsertions into Ideological Circuits.i Insertions into Ideological Circuits included the Coca-Cola and Banknote projects (1970). For the sometime, he printed Coca-Cola bottles with an explanation of the project, with texts such every bit "Yankees Get Home." For the latter, he stamped paper currency with messages including "Quem Matou Herzog (Who killed Herzog)?" After being marked past Meireles, objects were returned to circulation. When Mari Carmen Ramírez began using the term "Ideological Conceptualism"ii Ramírez cites Simón Marchán Fiz'due south use, in 1972, of the term "ideological conceptualism" to draw a tendency he was seeing in Argentina and Spain: "For Marchán Fiz, the distinguishing feature of the Spanish and Argentine forms of Conceptualism was extending the North American critique of the institutions and practices of fine art to an analysis of political and social issues." Mari Carmen Ramírez, "Blueprint Circuits: Conceptual Art and Politics in Latin America," in Alexander Alberro and Blake Stimson, eds.,Conceptual Art: A Critical Anthology (Cambridge, Mass. and London: MIT Press, 1999), pp. 550–551. in the early 1990s in her landmark essay on Latin American conceptualism, she delineated these differences.3 Mari Carmen Ramírez, "Design Circuits: Conceptual Art and Politics in Latin America," in Alexander Alberro and Blake Stimson, eds.,Conceptual Art: A Critical Anthology (Cambridge, Mass. and London: MIT Press, 1999), pp. 550–551. And although we need to be able to analyze how Latin American artists can be understood inside a global field of conceptualisms, we must likewise account for how their work developed in contexts entirely divide from centers, which tin can involve resisting the temptation to compare with what was occurring, for example, in New York. Fine art historians must enrich the narratives of what Luis Camnitzer calls Latin American conceptualisms' "local clocks."iv Luis Camnitzer,Conceptualism in Latin American Art: Didactics of Liberation (Austin: University of Texas Press, 2007). As scholarship on Latin American art expands and diversifies, we must also inquire if conceptualism remains a useful descriptor. Can it account for our growing understanding of artistic experimentation during this exuberant and expansive period? On February 20, 2013, the C-MAP workshop considered the uses and abuses of the term "conceptualism" and its variants.

Conceptualism or Conceptual Fine art?

"Conceptualism or Conceptual fine art?" was one of the questions brought upwardly in the workshop. I prefer conceptualism with a small "c," because it is unimposing yet still claims a identify for Latin American artists within the global field of the 1960s and 1970s. Advocates for small-c conceptualism include Luis Camnitzer, who prefers it because it does non wield the say-so of a motility as the term "Conceptual fine art" does. Nor does conceptualism require artists to brand fine art objects.5 Camnitzer makes this point with his description of the "aesthetic political" practices of the Uruguayan guerilla group The Tupamaros. Ibid., pp. 44–59. By refusing to quantify fine art's development, information technology likewise avoids the advanced rhetoric of rupture and progress. Conceptual fine art's broad historical application has too been questioned past other historians. And a rough consensus has formed that, considering it is a historical concept theorized by Joseph Kosuth and the Art & Linguistic communication group, it is simply really relevant to New York and London of the belatedly 1960s.6 Alex Alberro, Blake Stimson, and Benjamin Buchloh all draw this stardom. See Alberro, "Reconsidering Conceptual Art, 1966–1977," xvi–xxxvii; Stimson, "The Promise of Conceptual Art," xxxviii–Iii; and Buchloh, "Conceptual Art 1962–1969: From the Aesthetic of Administration to the Critique of Institutions," pp. 514–537, inConceptual Fine art: A Critical Anthology.

Follow-upwardly questions past C-MAP participants asked what should and should not be encompassed within histories of conceptualism in Latin America. They included:

What is the archaeology of conceptual practices in Latin American countries? Can the term "Latin American conceptualism" account for the complication of genealogies of conceptual and experimental practices that accept roots in kineticism, informalism, physical art and poetry, neo-dada, and automobile-destructive exercise, to proper name but a few? The curt answer is "probably non."

"To what extent do neo-dada and neo-surrealist practices betwixt the late 1950s and 1960s belong to a genealogy of conceptual practices? Are we are trying today to recuperate those practices as proto-conceptual when they were not?"

While conceptualism tin aid define the limits of a period and its concerns, employing it equally the starting point for a historiographical process raises doubts about the art historian'southward chore. Should it be that of tracing origins and genealogies? The term "conceptualism" tin can reproduce and perpetuate the prejudices of art history. Its failure to account for kineticism, informalism, physical fine art and poetry, as well as other fundamental tendencies proves that, instead of encompassing the histories of other experimental practices in Latin America, conceptualism represses them.

Some other question from C-MAP participants raised doubts nigh the capacity of conceptualism as a term to map an acceptable art history of experimental practices in Latin America:

What methodologies of research might permit specific histories to sally while not losing the international, transnational, and networked dimensions of artistic communications from the 1960s to the1980s?

This question cautions us to advisedly judge how we use conceptualism to historicize Latin American fine art. But it also suggests that conceptualism equally well as other global rubrics should not exist abased entirely. What we need are methodologies that can simultaneously analyze episodes from vertical and horizontal vantage points—verticality being the hunt for origins, the archaeological job of setting art history to local clocks; and horizontality the comparative task of identifying transnational points of contact and shared concerns. Alas, the almost pressing preoccupation voiced in all of these questions may exist summed up with the question: how can nosotros employ methods that locate artists and their piece of work within a time and place that is both specific and transnational? In this scenario, the globalization that imposes terms similar "conceptualism" would need to exist unpacked and understood as what John Tomlinson has called "circuitous connectivity."7 John Tomlinson,Globalization and Civilisation (Chicago: Academy of Chicago Press, 1999).

Dematerialization

C-MAP workshop participant Luis Enrique Pérez-Oramas questioned the overreliance on the idea of the dematerialization of art. Pérez-Oramas argued that the notion was based on illegitimate claims from the beginning, because dematerialization denies the fundamental materiality of language. "I think we urgently need to deconstruct the idea of dematerialization," he contended. Linguistic communication-based art "…doesn't hateful that fine art is dematerialized. The entire constellation of thinking that built modern and contemporary linguistics stresses the materiality of language as a style to dismantle the humanist ideology of the purity of ideas." The deployment of language in works past Clemente Padín, Edgardo Antonio Vigo, Carl Andre, and Lawrence Weiner supports Pérez-Oramas's business organization.

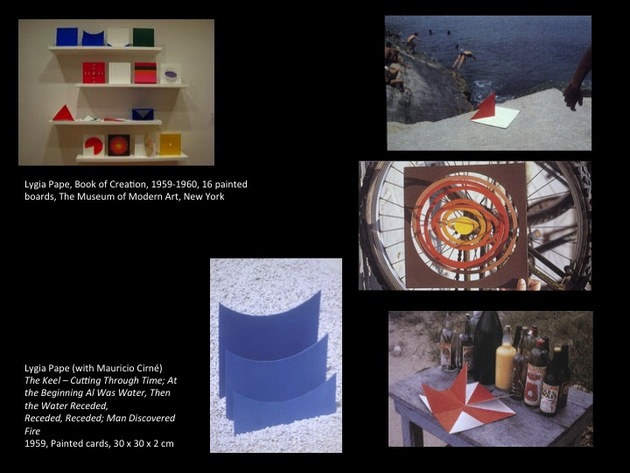

Dematerialization—no doubtfulness linked to the urgency of Lucy R. Lippard's political stance when she coined information technology with John Chandler in 1968Lucy R. Lippard and John Chandler, "The Dematerialization of Art," inConceptual Art: A Critical Album, pp. 46–50.—is undergoing a reevaluation. Fifty-fifty the recent retrospective of conceptualism based on Lippard's bookSix Years: The Dematerialization of the Fine art Object framed its task every bit "materializing."ix One reason Brazilian Neo-Physical artists have been absorbed nether the rubric of conceptualism is that they make it impossible to deny the materiality of experimental art during the 1960s and 1970s.

"What are the problematics of interpreting Neo-Concretism as proto-conceptualist considering of a desire to digest Brazilian artists into a global art history?"

The Brazilians also prove that dematerialization has been traded for participation. Seeing participation equally a key concern is then useful because through its agile date of the viewer-participant it reinserts subjectivity into the audience'due south experience of conceptual fine art. Its historical importance, even in New York, can be seen in the pages of the book Kynaston McShine published to accompany his showInformation in 1970. McShine emphasized the participatory more than annihilation else in his essay for the book, describing the "attitude" of the artists as "friendly" and their work as facilitating "experiences which are refreshing" and "therapeutic."8 Kynaston McShine, "Essay," inInformation (New York: The Museum of Modern Art, 1970), pp. 138–141.

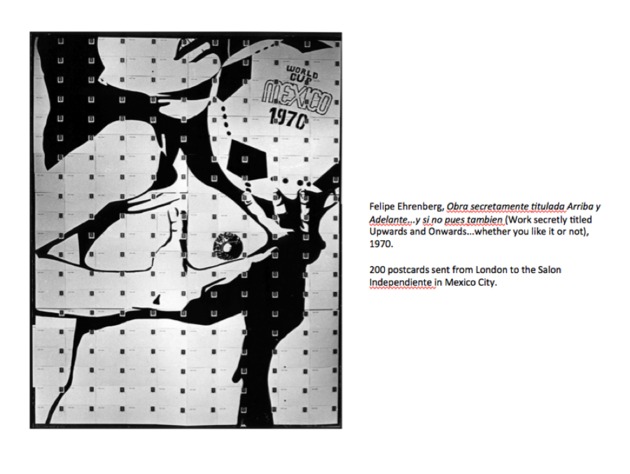

One of the most fascinating proposals of conceptualism—especially conceptualism conceived far from New York—was its incorporation of the methods of global advice into its constitutive textile. Artists working outside of geographic art centers were necessarily more practiced at using systems of distribution than their peers. This sense of the globe as artistic context is expressed by the work of artists associated with the Centro de Arte y Communicación (CAyC) in Buenos Aires, with Clemente Padín and Felipe Ehrenberg's mail fine art and magazine projects, among others.9 The CAyC, founded in 1968 past Jorge Glusberg, was a centre for experimentation in art and new media. Glusberg's complicity with government abuses under the dictatorship is the subject of important research by Carmen Ferreyra. Looking at the books, journals, and postcards that record these projects—many of which are housed in The Museum of Modern Art's Library—likewise reminds us that materiality was central to the meaning of even the most ephemeral of media-based proposals.

Arte No-objetual

In the stop, when they are not excavation for archaeological evidence, art historians should be tracking terms dorsum to their historical origins. "Arte no-objetual," coined past Juan Acha in the 1970s to account for experimental practices then developing in Latin America, is a perfect case in betoken. The Peruvian-born Acha theorized the concept while he was in Mexico City working with Los Grupos on experimental practices that incorporated performance, media art, and other imperceptible and interventionist tactics. When Acha convened a conference of scholars from Latin American countries in 1981 to fence the question of how to define Arte No-objetual, the answers encompassed new media, functioning, and traditional craft and artesania. Arte No-objetual's antagonism against internationalism and its markets was key. Fifty-fifty now, information technology is hit that when scholars invoke it to draw experimental practices of the 1960s,'70s, and '80s, Arte no-objetual even so conveys this antagonistic posture.

Miguel López, who has so productively interrogated the terms nosotros apply to describe experimental practices in Latin America, has urged us to revisit Acha'southward Arte no-objetual. He has besides reminded us that subject formation and identity politics are what are ultimately at stake in these debates. Questioning the comparative methods that accept forced Latin American conceptualists into the office of authentically political artists, López has argued that these methods take imposed essentialism in merely another course. Looking to compensate for conceptualism's failure to intervene in life, critics in the United States plow to Latin America. López urges us instead to observe what artists already know: subjects must constantly reinvent and transform themselves in response to fields that alter and morph. Thus the art historian should stop trying to nail downwardly the discipline and instead begin to study the complexity and dynamism of the field.

Source: https://post.moma.org/conceptualism-dematerialization-arte-no-objetual-historicizing-the-60s-and-70s-in-latin-america/